In December, in Don Garber’s state of the league address, the Major League Soccer commissioner made an astounding claim: MLS clubs were collectively losing over $100 million per season. The announcement was widely scoffed at, and seen as posturing ahead of the upcoming collective bargaining negotiations.

As someone who once flirted with an accounting career, going so far as getting a diploma before realizing how bored I was preparing myself to be for the rest of my life, I know that the profits or losses a company declares in its financial statements don’t necessarily equate to cash gains or losses. That said, it’s discordant to see MLS simultaneously crying poor and announcing multi-million dollar signings of players like Steven Gerrard, Jozy Altidore and Sebastian Giovinco. I’m going to do something in this article I don’t usually do: take MLS at its word. The league is in awful shape, losing over $100 million per year, and its solution is to keep buying increasingly more expensive players. Is this a good strategy?

First, let’s look at who these expensive players are, and how much they’re making. We’re going to look at 2014 numbers, because it’s obviously too early to know what effect the latest crop of players will have on the league. Here is every player that made $1 million or more in 2014:

- LAG – Landon Donovan ($4,583,333)

- LAG – Omar Gonzalez ($1,250,000)

- LAG – Robbie Keane ($4,500,000)

- MON – Marco DiVaio ($2,500,000)

- NER – Jermaine Jones ($3,252,500)

- NYRB – Tim Cahill ($3,625,000)

- NYRB – Thierry Henry ($4,350,000)

- ORL – Kaka* ($7,167,500)

- POR – Liam Ridgewell ($1,200,000)

- SEA – Clint Dempsey ($6,695,189)

- SEA – Obafemi Martins ($1,753,333)

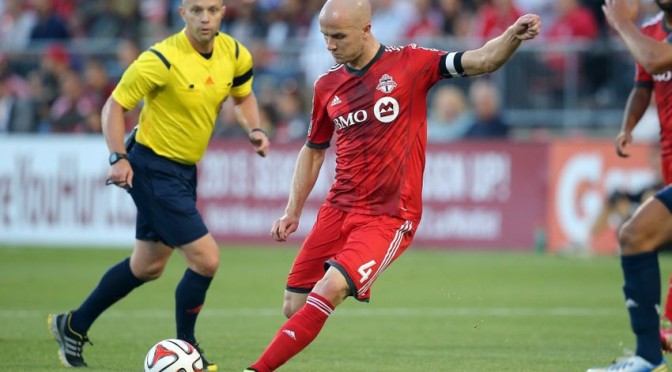

- TOR – Michael Bradley ($6,500,000)

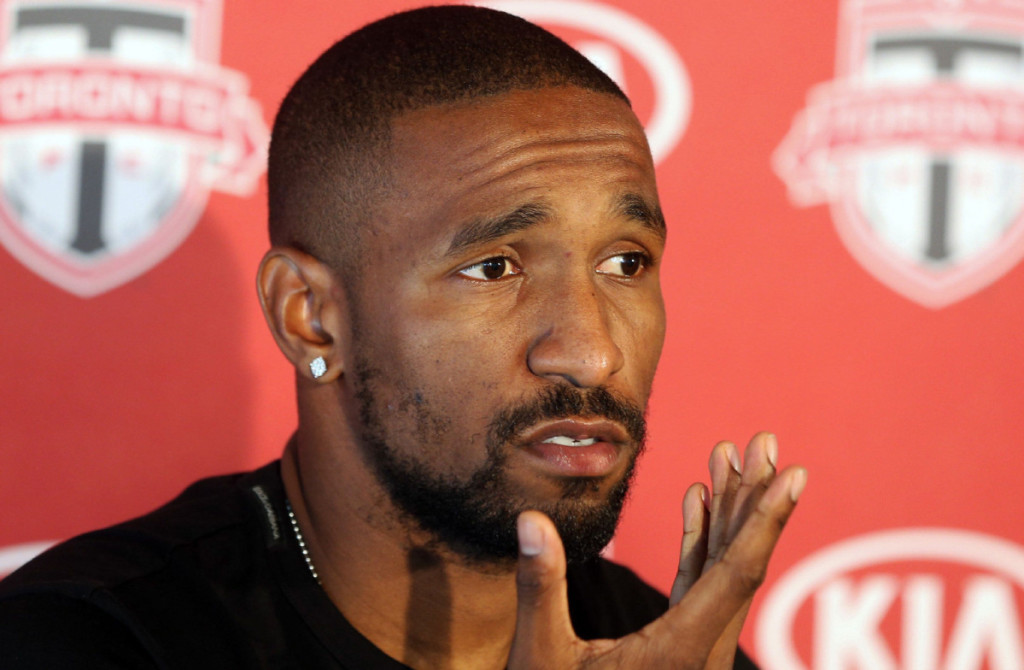

- TOR – Jermain Defoe ($6,180,000)

- TOR – Gilberto Junior ($1,205,000)

- VAN – Pedro Morales ($1,410,900)

*It’s not clear how much of Kaka’s salary was paid by Orlando, as he was loaned to Sao Paulo, but again let’s take the numbers provided at their word.

Only nine out of twenty-one clubs had a million-dollar player on their roster in 2014. (We’re counting Orlando and NYCFC because the player’s union says they had guys earning salaries.) Only four had more than one. In total, fifteen players, spread over fewer than half of the league’s clubs, accounted for just over $56 million dollars in salary, or over half of the league’s losses. Is the league likely to recoup these losses?

Let’s start with the largest cash infusion in the league’s history: its new domestic television deal worth an estimated $90 million per year. This type of money likely isn’t thrown at the league without the star power of some of the names in the above list. Subtracting the money from the previous TV deal, we can expect the league to offset about $60 million of its losses just on new TV money in 2015. More, if Sky Sports paid anything significant for the rights to broadcast two games a week in the UK. As terms of the UK deal, unlike the domestic rights deal, were not disclosed, I am assuming Sky did not need to pay much, and MLS was happy enough just getting their product on British television. We’re down to a $40 million shortfall.

Now things get slightly murkier. How much of an effect do players of this calibre have on attendance? This is difficult to measure, because winning tends to have a positive effect on attendance and it’s difficult to pin how much of a team’s success is attributable to its most expensive players. The Galaxy, for instance, brought in Robbie Keane in 2011 and saw a nearly 2,000/game bump in attendance, but they were riding a 2010 Supporters Shield victory, and won a second one in 2011. How much of that attendance bump is “oooh, Robbie Keane” and how much is “oooh, I like winning teams.” Let’s see how the rest of the clubs fared.

- Montreal signed Di Vaio in 2012 and saw diminishing attendance for the two years thereafter.

- New England’s attendance increased by about 1,850/game, but they didn’t win the Jermaine Jones lottery until September.

- New York saw their attendance soar by about 6,000/game when they signed Henry in 2010. The arrival of Tim Cahill in 2012 did not have a similar effect; the club lost 1,800 fans that year.

- Portland has seen attendance increase every year, but that’s as much due to capacity increases and pent-up demand as it is Liam Ridgewell.

- Seattle experienced a small spike in their first half-season, and a small decrease in their first full season, after the additions of Dempsey and Martins. They’re up about 500/game in total.

- Toronto lured back 4,000 disenfranchised supporters with their bloody big off-season spending spree in 2014.

- Vancouver saw a modest 400/game bump after Pedro Morales was added.

Let’s be generous here and say that those attendance bumps are permanent over the contract of the player. You’re going to get maybe 10,000 more butts in seats league-wide, on average, which translates to $12-15 million in extra revenue, depending on the average ticket price of the clubs doing the buying. In the best-case scenario, we’re still left with at least a $25 million shortfall.

Now how generous do you want to get with things like merchandise? Let’s assume every one of those 10,000 extra attendees buys a jersey for their new favourite player. At $140 for a customized jersey and (pure guesswork here) a 30% markup. You’re talking less than half a million dollars in extra revenue. In fact, you would need to sell 773,755 extra jerseys (at my guesstimate figures) to make up the shortfall.

Colour me extremely skeptical that the league is managing to approach breakeven on these players.

So how much of a problem does the league have? Its single-entity nature means the league can distribute its losses somewhat, and it’s probably only going to average a $1-2 million loss per club. The problem, though, is the league is setting itself up to be similar to a European league, with a small number of dominant teams at the top spending all the money and getting all the results. Look at the champions since the league started loosening restrictions and allowing multiple Designated Players: three out of the last four Supporters Shields and MLS Cups have been won by clubs with more than one millionaire salary. In the big European leagues this works ok. There are other things to play for. Relegation battles, cup competitions that the big clubs don’t always take too seriously, the prospect of Champions or Europa League play if you can get hot and sneak into the top five for a year. In MLS you have a race to the bottom for the right to draft next year’s stand-out NCAA player. Woohoo.

I worry that we’re seeing the effects. The league has just folded its third franchise in only nineteen years of existence. Rumours are swirling that season ticket sales in Montreal were horrendously bad, though perhaps their dramatic upset win in the Champions League quarterfinals will improve that somewhat. A glance at the stands in Houston, Dallas, DC and even Philadelphia shows that many clubs can’t even sell out their barn for opening day. The TV numbers league-wide remain terrible.

This is a league that once enjoyed modest success and growth with their devotion to parity. Nine different teams won the Supporters’ Shield in the league’s first thirteen seasons. Eight different clubs won MLS Cup over the same period. There was a reasonable chance that even if your club sucked one year, it could be good again the next. The league has gone away from that and it’s not at all clear that a lack of parity is in the best interests of anybody but a select few clubs.